2 Great Mindshift – The Transformative Power of Ideas

“The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds.” (John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 2007)

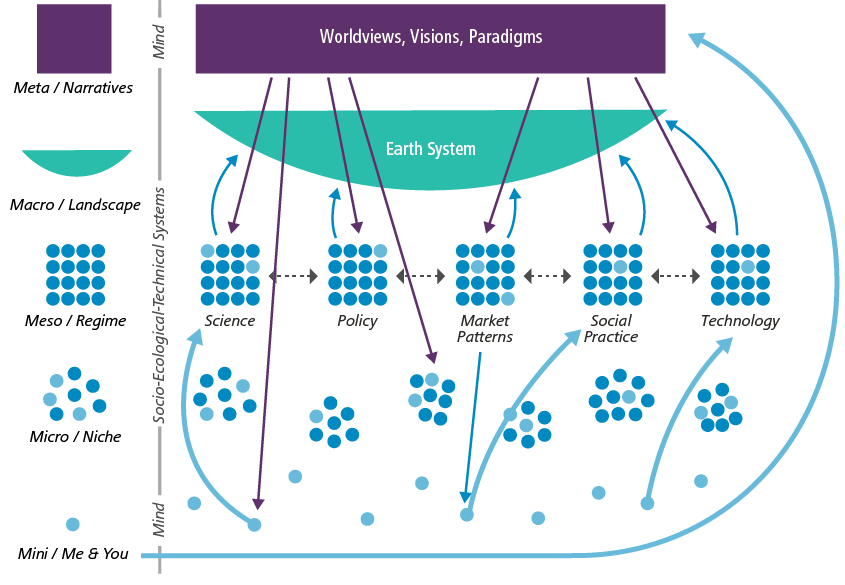

Transformation research occupies itself with the question of how large-scale system change happens. Chapter 2 discusses different approaches in this field and amends one widely used model, the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) by Frank Geels, with insights from the perspective of a political economist. The MLP draws on structuration theory in sociology and distinguishes three different levels at which societies are organized according to their degrees of changeability.

- At the niche level experiments or pioneering innovations are undertaken by small units or ’situated groups’. They can rapidly change and deviate from the prevailing context, because they are less dependent on other levels of the system.

- The overarching level is that of the regime and is composed of well-established practices, rules, institutions, and technologies that govern social interaction at the societal level. Changes in one of these institutions will impact many people and processes at the same time, which makes the task more challenging.

- On the landscape level we find slowly changing, rather exogenous development trajectories like environmental conditions, major infrastructure, deeply embedded economic institutions like the market system, and worldviews or social values. Landscape developments form the backdrop for developments at the lower levels.

The model (seen below) depicts the dynamic developments at all these levels as resulting from simultaneous processes in diverse subsystems that influence each other and react to changes or shocks in connected or overarching systems. The landscape level is impossible to change purposefully in the short term, but it can bring about and be subject to shocks (such as natural disasters) that lead to rapid change at regime or niche levels. Changing configurations create different drivers and scope for transformations so that many changes at lower levels also trigger reactions at overarching ones.

From this point of view, transitions to sustainable development are conceptualized as long-term, multi-actor processes involving interactions among citizens and consumers, businesses and markets, policy and infrastructures, technology and cultural meaning. Actors or groups with different interests or views might resist via direct intervention, but resistance also comes in the form of various types of path dependencies. These range from the big infrastructures that are difficult or take a long time to change to the higher transaction costs of reorganizing production processes; from technological breakthroughs or fear of loss through social roles to mental barriers in seeing possible different solutions. All of these stabilize the status quo. Given the pervasiveness of such path dependencies system scholars argue for radical incremental change strategies: too much change in too short a period of time is likely to cause a lot of resistance or might risk the system’s functioning all together.

When looking for drivers of transformation most transition studies focus on more visible and tangible types of path dependencies to identify possible levers for change. The list of ‘main ingredients’ for successful transformation by system innovation practitioner Charlie Leadbeater does, however, shows that the origin of intentional change strategies is how actors interpret the situation:

- Failures and frustrations with the current system multiply as negative consequences become increasingly visible.

- The landscape in which the regime operates shifts as new long-term trends emerge or sudden events drastically impact availability or persuasiveness of particular solutions.

- Niche alternatives start to develop and gain momentum; coalitions start forming which coalesce around the principles of a new approach.

- New technologies energize alternative solutions, either in the form of alternative products or as new possibilities for communication and connection.

- For far-reaching regime change (rather than small adaptations and co-optation by the old regime), dissents and therefore fissures within the regime itself are key. In joining coalitions for change, they will help bring the system down or at least significantly change its current set-up and development dynamic.

The loss of persuasiveness in step 2 and also expressing a new approach and principles to coalesce around (step 3) are crucial factors of purposeful and collective activity. Individual mindsets and social paradigms are a society’s ‘software’: the reservoir of ideas, norms, values and principles actors draw on when creating technologies, institutions, laws, business models and individual identities. Thus, a transformational sustainable development agenda needs a new ‘software’ to open up the imaginary and thus political space for radically different new approaches .

Given the transformative, if often overlooked power of ideas, I added two levels to the original MLP: the mini-level of individuals that make up any institutional setup plus the meta-level of mindsets that cuts across and mediates between the individual, niche and regime levels.

The purple and blue arrows illustrate how ideas function as the software that hold societies together. Critical political economist Antonio Gramsci in his Selections from the Prison Notebooks (1971) spoke of hegemony when he pointed out how such a reservoir of ideas, norms, values and principles lend structural power to solutions or interests that present themselves as in line with the prevailing software. He further emphasized the need for a counter-hegemonic common conception of the world, an alternative imaginary of a desirable future. Gramsci saw this as critical if ‘dispersed and shattered people’ were to organize into a collective will for political change.

This is why the purple arrows stand for the hegemonic paradigm or software that is well embedded in regime structures as well as in niche projects. At the same time, individual mindsets (the light blue arrows) might carry alternative imaginaries or paradigms that inform their pioneering strategies. In addition to experimenting with or showcasing practical solutions in line with the new paradigm, individuals can engage in counter-hegemony work and widen the acceptance and support for repurpose strategies: highlight the faltering persuasiveness of an outdated software and put forward alternative sense-making or meaning.

In the decades to come, the old iron cage economics paradigm and alternative paradigms will be struggling to fit the shape taken by what could become a Second Enlightenment. Our task is to develop the transformative literacy that can support a radical incremental transformation around the goal to recouple our economic processes with planetary and human wellbeing. This is what The Great Mindshift stands for.