5 Radical Incrementalism – Strategies for System Innovations

“The common theme throughout this strategy for sustainable development is the need to integrate economic and ecological considerations in decision making. They are, after all, integrated in the workings of the real world. This will require a change in attitudes and objectives and in institutional arrangements at every level.” (Brundtland Report Our Common Future, 1987)

These days, at least within the community of environmentally and socially interested people, we frequently hear about the need for radical or transformative changes. Unfortunately, this often goes along with dismissing incremental changes as insufficient. Yet system thinking highlights how juxtaposing the two approaches as entirely separate strategies does not help. What does help is to determine both the radicalness of the imagined outcomes (what do we deem necessary, desirable or possible) and the types of changes that are necessary to move in this direction. Little steps are important because existing path dependencies make massive or deep changes unlikely unless they are well prepared – through many incremental steps.

So we should neither stick the label ‘transformation’ on any amendment to the status quo, nor call each technological efficiency gain an ‘innovation’. Chapter 2 of the book shows that the literature on transformations to sustainability uses this label to describe a change in overall system dynamics: co-evolutionary changes in technologies, markets, institutional frameworks, cultural meanings and everyday life practices. As a result, it is not only the components that are changed, like less environmentally harmful products, but also the architecture of the system, the relationships between components of the system and the ideas about how things are best done.

So, if transformational change is defined as ‘radical’ because a system’s dynamics, components and architecture have been changed, two questions arise: 1) How can a radical degree of reconfiguration be intentionally pursued? 2) How can system dynamics be altered to the extent necessary without effecting collapse or rejection?

System innovation scholars answer these two questions by addressing the art of repurposing the system’s functioning in line with a changed view of what a good outcome entails. Radically updating this outlook and thus the system goals itself comes before the relevant steps, reconfigurations or innovations that bring actual performance into line with the new intentions. It means that radicalness in purpose is equivalent to holding a vision or belief of what could be possible if X, Y or Z was to change. This is an imaginary that ignites energy, commitment—and persistence in taking the many and diversified incremental steps required to get there.

The sustainable development agenda, for example, was born out of the insight that the radical development purpose of endless economic growth was destroying nature, not delivering on the human needs of all people today, let alone considering future generations and their needs. Tackling this grand challenge with a transformative rather than adaptive agenda can thus only be undertaken if accompanied by thorough scrutiny of how we understand long-term wellbeing of nature and humans. Development goals need to be redefined according to this new purpose and then be used to guide the design and evaluation of interventions and innovations.

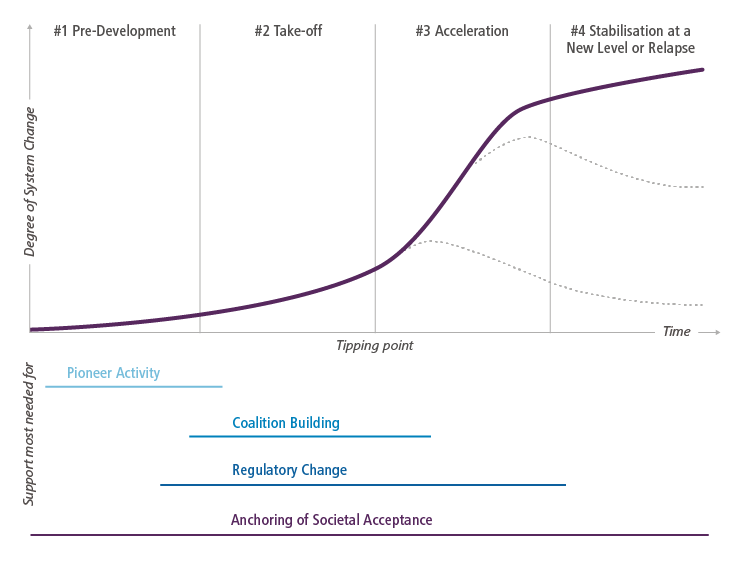

Iron cage economics describes how we are only now moving near such a great mindshift. Understanding transformations as radical incrementalism makes this a great window of opportunity. System changes are the result of a sufficient degree of departure from the status quo. Transformation research offers a 4-phase-model or S-curve to show how these build up when sufficient alternatives become viable and enough support is generated to make return to former path dependencies impossible.

By highlighting which type of activities are crucial in which phase the model highlights the importance of individual mindsets and social paradigms: without this, strategic development of alternative ideas and pioneering innovation is unlikely to take place. Coalition building and finding support for regulatory changes both depend on communication and sharing of visions, narratives, interests and evidence.

The outcome of acceleration phases in which a lot of change becomes possible in a short period of time is determined by the ideas and power of the people and networks engaging in it. And the stronger a new common idea of a desirable outcome is anchored, the more anchored a great mindshift itself will become and the more difficult it will be to stop the unfolding of systemic change – even if single events or plans fail. With this book, I aim to spread transformative literacy so that crises stand the chance to be turned into opportunities for recoupling economic processes with human and planetary wellbeing.