7 Recoupling – A New Imaginary for Sustainable Prosperity

“Recognizing the importance of mindsets in the sustainability transition allows an opportunity to reflect and examine underlying assumptions, identify shared values and cultivate common ground. Each of these contributes to defining the shared goals and the compelling visions necessary to bring these changes about.” (UNEP GEO5 Report, 2012)

Karl Polanyi described the emergence of market societies as a great transformation, because it not only fundamentally changed the organization of economies, but also because it was driven by an overhaul of key values, ideas and beliefs about how the world actually functions and how it should function. Polanyi points to many influential philosophers and emerging economists of the 18th and 19th centuries and claims they were driven by the ‘stark utopia’ of a self-regulating market system when imagining how to organize societies. He called it ‘stark’ because in this imagined future land (nature), labor (humans) and capital (money) were conceptualized and governed as input factors or ‘fictitious commodities’ with the only purpose being to be bought and sold. He called it ‘utopian’ because believing that an economic system geared to endless competitive growth would not damage the real qualities of its fictitious commodities depended on serious denial of the reality of social and natural life.

Today, 250 years after the stark utopia emerged, some of its key ideas and concepts—like ‘gain’ being the prime human motivation, ‘utility’ a good measure for well-being and ‘capital’ a useful container term for everything that might be needed in production processes— still form the basis of most economic analyses and calculations. Applying them means that the metrics calculate ‘growth’ and equate growth with progress – even when that means that nature is destroyed to a degree that threatens to tip ecosystems out of balance. Even when humans suffer physically and mentally in their highly pressured work conditions or are made ‘redundant’. And even when a financial system has become a speculative casino that enriches a few beyond what’s imaginable, but keeps money and investments from reaching those without purchasing power: the poor.

Of course there are a lot of politics and interests behind these events and not only a stark utopia. But sociologists speak of the imaginary when referring to a set of values, institutions, laws and symbols through which a social group or society imagine their social whole. As deep-seated ways to make sense of the world, imaginaries create a common, mostly subconscious pattern of perception. They underpin typical ways of living and influence how people anticipate their future existence.

In the sustainable development agenda, for example, proposed strategies and solutions invariably do not talk of replacing the purpose of development by something that is not in line with the utopia of endless economic growth. The primary agenda seeks to decouple economic growth from natural resource use and human-induced limits to productivity. Hopes for this decoupling rest on the next technological revolution and financial capital owners should not be regulated or taxed too much just so they can use their ‘animal spirits’ to drive this breakthrough forward

Evidence presented in chapter 3 shows that this iron cage effect of an old paradigm prevents the repurposing of economic systems. Ramping up the old vision, means and methods cuts short of a new imaginary. So chapter 4 is dedicated to a review of four pioneering movements that explicitly bid the stark utopia farewell:the Economy for the Common Good (a prominent business initiative born in Austria), Transition Towns (an urban community initiative born in the United Kingdom), the Commoning Movement (civil society initiative born in the United States) as well as the Bhutanese Gross National Happiness (GNH) Framework (a role model for government initiatives that want to go Beyond-GDP with other performance indicators, e.g. compared with the Better Life Index of the OECD).

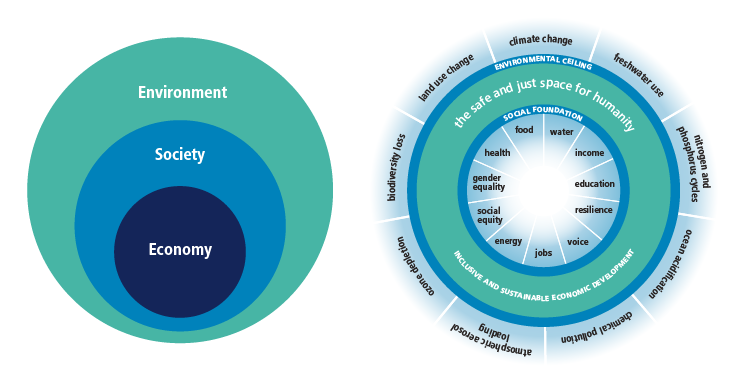

Although I would not venture to state that one can identify a clear-cut new paradigm or streamlining development purpose like ‘economic growth’ I was surprised by the common ground between 21st century science in chapter 3 and the practice initiatives outlined in chapter 4. The great mindshift that runs through all of them is one of ‘embedded systems’ where ecological systems are the basis of societal systems and the economy no longer an overarching machine but subordinate means to align natural and human wellbeing. There are many possible variations how that alignment can be achieved and human reflexivity holds the potential to update the chose solutions when circumstances are changing. The ‘doughnut’ by Kate Raworth has become one powerful symbol for this imaginary, depicting the corridor of safe and just development that an economic system should enable humanity to evolve within.

When searching for a new common vision that can inform varied radical incrementalism strategies I would thus go as far as suggesting that the new imaginary for sustainable prosperity is one of recoupling economic processes with human well-being and nature’s laws. This is radically different to a goal of decoupling otherwise unchanged economic growth through efficiency revolutions. Instead of intending to repair some nature (if no substitute input factor can be found) and redistributing some of the utterly inequitably generated wealth (if welfare policies do not stifle growth) these solutions seek to deliver sustainable prosperity by design.

The question of course arises how we get there. System thinking suggests focusing energy on a few leverage points and observing how this changes dynamics and creates room for further changes. Given that market system societies as designed today depend on more economic growth for their social security programs to function and economic stability to prevail, the radical incremental strategies for the imaginary of sustainable prosperity might best focus on double-decoupling:

- Decouple the production of goods and services from unsustainable, wasteful or uncaring treatment of humans, nature and animals (do better).

- Decouple the strategies for human need satisfaction and protection from the imperative to deliver ever more economic output (do well).

The latter decoupling has been given much less attention because the worldview informed by the mainstream economic paradigm cannot even countenance it. But 21st century science improves transformative literacy and creativity by showing that human needs are not limitless and that social security systems or monetary systems do not have to depend on continuous economic growth. They also show which economic strategies would better reach people that are desperately in need of more goods and services (but due to their lack of purchasing power in the market system struggle to access).

Download chapter 3 or 4 of the book