1 Reflexivity – Humans Make History

“In the middle of the twentieth century, we saw our planet from space for the first time. Historians may eventually find that this vision had a greater impact on thought than did the Copernican revolution of the sixteenth century, which upset the human self-image by revealing that the Earth is not the centre of the universe. From space, we see a small and fragile ball dominated not by human activity and edifice but by a pattern of clouds, oceans, greenery, and soils. Humanity’s inability to fit its activities into that pattern is changing planetary systems, fundamentally. Many such changes are accompanied by life-threatening hazards. This new reality, from which there is no escape, must be recognized—and managed.” (Brundtland Report, Our Common Future 1987)

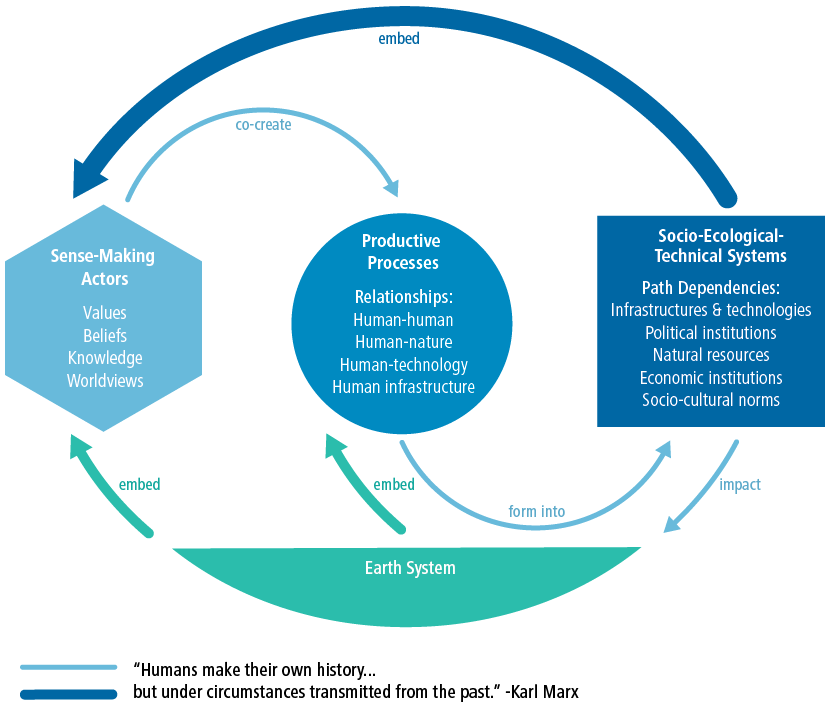

In order to make sense of the world humans create ideas and stories about why they are here, what the purpose of their life-journey is, and how to relate to their human and natural environment. The results are mindsets that lie at the heart of individual identities and social paradigms or imaginaries that shape socio-political development processes. These imaginaries include widely accepted common sense, canonized knowledge, and cultural narratives – the human self-image that is drawn upon to define human roles, to design suitable technologies and to agree institutions for cooperation.

So these immaterial aspects of history-making become reified: ideas and stories solidify as structural or even material features of the context in which thinking about the future, observing and being happen. Thus, subjective ideas and social imaginaries are intricately linked with the ‘objective’ world. They can be a source of vision, innovation, creativity and flourishing progress, but also a source of mental barriers, strategic power or even forceful domination.

Understanding the way ideas impact the creation of material structures and how these in turn impact what could be called the ‘patterned freedom’ of human development is the core of ‘reflexive’ social sciences. Reflexivity is a uniquely human capacity that enables people to become aware of biases and the effects of socialization, and to identify the ways that habits, path dependencies and guiding stories drive societies along development routes that are not (any longer) in line with broader goals and aspirations. Seeing the new reality of Earth being an intricate web of life rather than an endlessly exploitable resource and the consequent agenda of sustainable development is a prime example of reflexivity.

The magnitude of contestation that this new reality brought to prevailing common sense and deeply embedded and materialized paths of industrializing (namely mass exploitation, production and consumption) explains why terms like a Great Transformation or upset of the human self-image were part of this agenda since the beginning. Reassessing the underlying assumptions, ideas and beliefs upon which social processes and institutions have been built, justified, maintained and adapted does empower humans to break free from them if necessary. But breaking free is also a highly political process which particularly those people might find less appealing who are comparatively well off or privileged under given circumstances.

A reflexive approach therefore takes ideas, beliefs and the current state of scientific evidence as integral parts of making and shaping the future. Ideas, beliefs and scientific evidence justify and rationalize the logic and merit of human motivations and activities used to fulfill needs or pursue interests. The outcomes are identities and habits that last beyond the actual activities that formed them and influence future aspirations, perspectives and habits.

Sociology has specialized in researching these structures and Norbert Elias’ book The Civilizing Process (1982) became one of the most influential sociology books of the twentieth century. It explores the relationship over time between power, behavior, emotion and knowledge and concludes that circumstances do not occur as ‘phenomena’, nor do individuals encounter them in this way. Instead circumstances are manifestations of changing relationships between humans and between humans and their environment. Transformation scholars describe the complexity of those relationships as path dependent socio-ecological-technical systems, but they sometimes forget to explain where they came from in the first place. Elias’ term ‘sociogenesis’ describes how these relational system structures emerge over time and he links it with the process of ‘psychogenesis:’ prevailing circumstances mold individual learning, identity formation and sense-making.

This brings us to the reality that humans are both the subject and the object of history. A great transformation of structures or circumstance will be accompanied by a great mindshift amongst the actors involved. For pursuit of good lives within the new reality this is great news. Iron cage economics and its commodification of all aspects of life is an incredibly strong trend. But human freedom lies exactly in developing the transformative literacy that enables people to deconstruct the emergence and perpetuation of processes, patterns or coalitions behind this trend. Human freedom also lies in recoupling economies to serve sustainable prosperity, rather than economic growth.

Reflexivity rejects claims like ‘the end of history’ or ‘there is no alternative’. Civilization did not cease to evolve after the first Enlightenment and modernity. This is proven not only by social sciences of the 21st Century, but also by quantum physics: our world is constantly evolving through flows of information and energy. The German language has a great word for ‘reality’ to capture this information-based interplay: Wirklichkeit. Wirken means to ‘seem’ and ‘appear’, but also ‘have an effect’ or ‘operate.’ So whilst power and influence seem to be very unevenly distributed today, every one of us can still exercise a little force in shaping the future. This is the message that the book wishes to deliver.