3 Repurpose – The Challenge of System Innovation

“Even if we succeeded in pushing our technological capabilities to the utmost, without doing something else, in a few decades we are likely to end up in a world that would offer reduced opportunities for our children and grandchildren to flourish.” (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Back to Our Common Future 2012)

The current extent of environmental degradation, climate change, increasing gaps between poor and rich and unprecedented concentration of power and wealth in private hands show one thing: doing more things more efficiently is simply not enough when the goals and ends of a system are outdated. ‘Doing something else’ is the distinguishing feature of a transformational agenda. Chapter 2 of the book argues how this insight demonstrates that the ultimate source of intentional transformative change lies in humans’ sense-making and their potential to be reflexive creators of history.

Humans engage with one another and with nature in order to produce the goods and services deemed necessary or beneficial to their well-being. Such engagement involves the creation of supportive institutions and technologies, incentives and norms. These generate structural path dependencies, which in turn shape and constrain the possibilities of future developments. So understanding the purpose around which our current systems are built will enable us to see where this purpose might be outdated and thus our institutions and technologies, incentives and norms have become an iron cage, inhibiting freedom and ingenuity in finding up-to-date solutions.

The sustainability agenda is a prime example of such inhibiting effects. The original documents that underpin the agenda called for the replacement of the conventional economic growth path with ‘sustainable development’ and defined sustainable development as that which meets ‘the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland Report Our Common Future 1987). From this emerged the often-cited ‘integrated perspective’, whereby economic concerns were to take environmental and social concerns into consideration.

But what happened? Instead of a thorough interdisciplinary endeavor to spur a paradigm shift that captures the purpose of sustainable development holistically, it was the iron cage economics that became paramount. Social and ecological concerns were inserted into economics’ commodification agenda so that yet more economic growth could pay for a technological revolution. This in turn would allow for even more growth by decoupling it from environmental damage, thus increasing the amount that could be redistributed to the poor. Checking for the actual quality of human needs and no-growth strategies to satisfy them was not in the cards, not even in very rich countries. Nor was focusing innovation emphases on how nature’s ability to replenish resources could be respected rather than substituted. In other words, ‘doing something else’ was excluded.

After 40 years of treating sustainability as something which is nice-to-have if economic growth permits, more and more recoupling initiatives are emerging that tackle the iron cage head-on. They make sustainability their core purpose around which economic, technological, socio-cultural and institutional setups are innovated. This includes the key values, ideas, principles, symbols and parameters that inform a great mindshift and new imaginary for future development. In doing so they operate in a space that system scholars would recognize as the highest leverage points for system change. In Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System (1999) Donella Meadows itemized twelve categories of leverage ranked by increasing order of transformative impact.

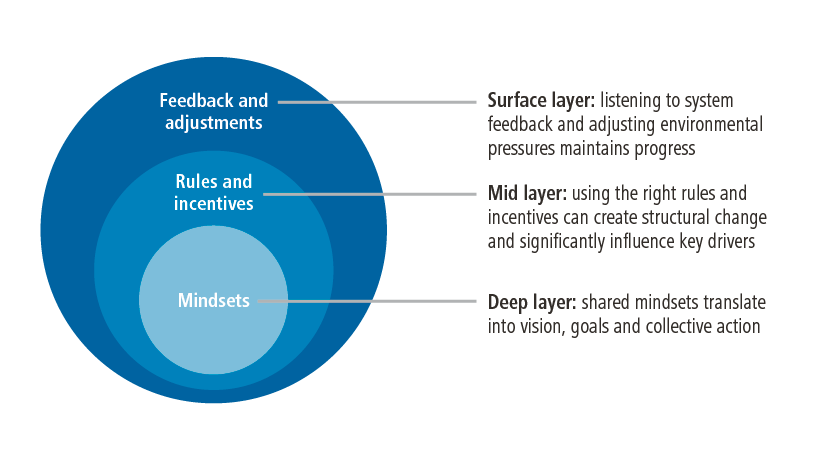

The graph illustrates that those can be distinguished by quality. At the surface layer are low-leverage policies and practice that the sustainable development agenda is famous for: subsidies, taxes, standards, and better accounting for key forms of capital. The mid layer is made up of more relational elements like the structure of information flows, feedback loops or the rules of a system, including its incentives, punishments and constraints. A lot of change can be obtained by working on this level. Transformational intent, however, emerges on the top of the list or deep layer of this graph: the goals of the system and the mindset or paradigm from which all of its contours and elements emerge and where the power to make history lies: by transcending paradigms.

Repurposing systems starts at the top of the leverage point list or the deep layer of system innovation. It will then, of course, require intense work of an often highly political character and the acceptance that it takes time. Seeking to change a system too swiftly or too drastically at once is likely to create self-defensive or destabilizing reactions. The art of repurposing a system is an agenda of radical incrementalism that requires the transformative literacy to find the right steps (no matter how small) and measures at the right time. And it puts human potential center stage: sense of purpose is a deep human need and a fantastic source of creativity, energy, collaboration and persistence.

Download Chapter 2 of the book