6 Transformative Literacy – Competencies for System Innovations

“Transformation or transformability in social-ecological systems is defined as the capacity to create untried beginnings from which to evolve a fundamentally new way of living when existing ecological, economic, and social conditions make the current system untenable.” (Stockholm Resilience Centre 2012)

The world is undergoing massive transformations: we need to change their qualities to achieve sustainable development. Analysis shows that even skillfully managed transformation processes can lead to very unsustainable outcomes, while very well-designed sustainability solutions can cause resistance or even turmoil in a system that is not ready for this change.

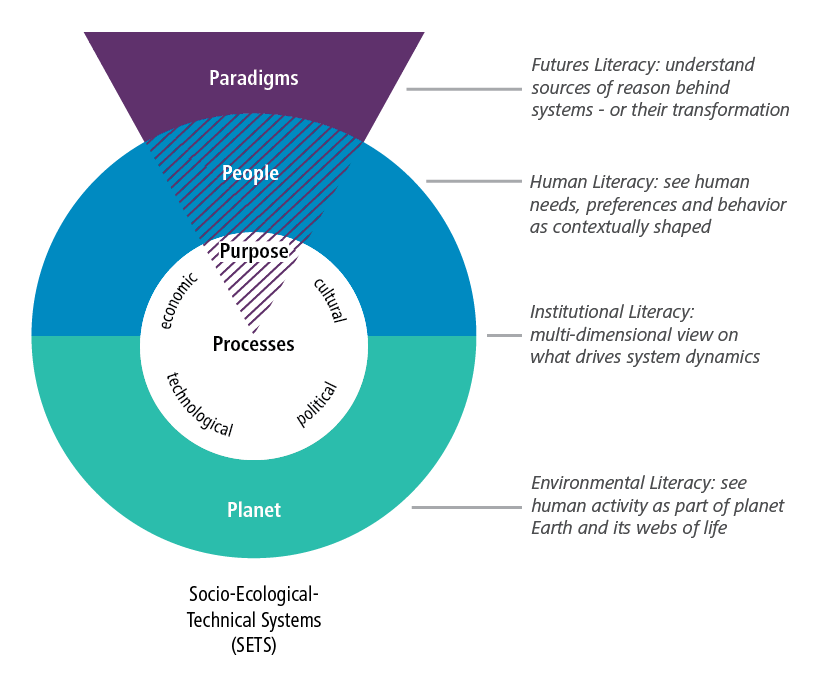

Designing effective repurposing strategies therefore requires what Uwe Schneidewind (2013) called transformative literacy: the ability to perceive, interpret and utilize information about societal transformation processes in a way that enables people to get actively involved in shaping these processes. Its focus on human-human relations following Roland Scholz’ (2011) call for better human-nature relations through environmental literacy. Environmental literacy is defined as the ability to read and utilize environmental information appropriately, to anticipate rebound effects, and to adapt to changes in environmental resources and systems, and their dynamics. The common denominator between environmental and transformational literacy is a critique of the search for sustainable development solutions that focuses too much on technological innovations and which hopes that amenable economic and political processes will ensure their adoption. Without understanding the ecological, cultural and social dynamics of a particular system actors will effectively ignore crucial drivers of or barriers to change.

Many sustainability transformation scholars share this perspective and provide holistic approaches for an understanding of current development pathways. To create the conviction and coalitions to break out of these pathways, however, chapter 5 argues that it is also important to add an understanding of the deeper sources of human perception, behavior and willingness to act.

The World Social Sciences Report 2013 went in this direction by introducing the term ‘futures literacy’: people’s capacity to imagine futures that are not based on hidden, unexamined and sometimes flawed assumptions about present and past systems (ISSC and UNESCO). Exposing blind spots will allow imagining and framing of radically different futures at times where something new and not more of the same is needed.

To the ability to understand and engage in transformation processes I therefore suggest adding the deeper dimension of reflexivity. Scrutinizing individual views and social paradigms for their framing effect on perceptions, interpretations and utilization of information about societal transformation processes is where the lever for radically different futures or untried beginnings lies. It is also the locus for intentional repurposing strategies: is the minimum wage promoted to safeguard enough purchasing power for continued economic growth (fix the symptoms of the old system) – or because the limitation of inequalities is conceived to be a new overarching goal (orchestrating a set of measures around a radical incremental transformative strategy)? Depending on this purpose decision the design and implementation process will vary, as will the likely coalitions of supporters.

In addition, sensitivity to mindsets is crucial for the active shaping of transformation processes. People with different worldviews will interpret the ecological, economic, political, technological and even cultural aspects of development very differently (e.g. sustainable development understood as green growth or as sustainable sufficiency). These lead people to argue for very different ‘best solutions’ (e.g. accelerate economic growth to increase monetary output to pay for the damage or reduce growth rates to prevent damage in the first place). Finding a new common understanding for multiple activities or initiatives to coalesce around is the role that a great mindshift plays in transformation processes.

Downplaying or even ignoring this deeper dimension of human reflexivity and purposeful action has been the crux of the sustainable development agenda: iron cage economics has led to a suite of well-intended (though often privilege-protecting) purported solutions. These help alleviate some symptoms by reducing relative environmental impact of products or directing some of the economic growth towards the alleviation of extreme poverty. But 40 years on, we can clearly see that this was not enough to tackle the root causes or deeper drivers of unsustainable trends.

The ability to transform goes beyond doing more of the same more efficiently or effectively. It means repurposing systems in line with ongoing evolution and Enlightenment. This requires sensitivity for multiple perspectives and a preparedness to deal with the power of hegemonic ideas. It also requires courage to hold one’s own mindset and paradigm lightly: since we do not operate in blank spaces, letting go is the flipside of creating something new.

Checking for all 5 ‘Ps’ that shape a system’s operation will ensure a future-oriented transformative literacy that opens up the imaginary space for solutions but at the same time prevents naivety about how quickly structural path dependencies can be unlocked. Obviously, not all of these literacy-competencies need to be mastered by one person. Rather, complex system research bids farewell to the idea of a single change-maker heroine. Collective or systemic leadership approaches show how different types of expertise and capabilities complement each other in a team effort that leads to more than the sum of the activities.

Download Chapter 5 of the book